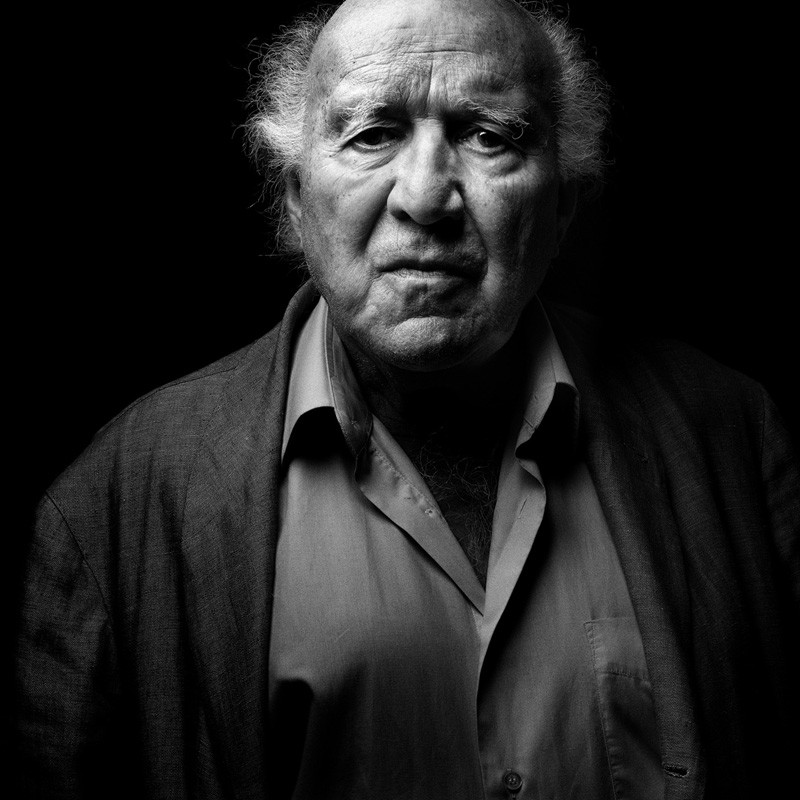

Interview: Denis Rouvre, Award-Winning Portrait Photographer

26th Oct 2012

A while back we started a series of interviews in which we talk to some successful and influential professionals from the multitude of fields that make up the photography industry. In the first interview in the series we spoke to Paul Cabuts, Academic Subject Leader In Photography at the University Of Wales in Newport and he gave us some great insights into his involvement with photography and how he came to be working as a University Lecturer.

For the second installment in this series we have been extremely lucky to have been granted an interview with esteemed French photographer Denis Rouvre. Renowned for his award-winning portrait photography, his work has been published and exhibited in France and internationally and he has released several books. Prizes won by Rouvre include a World Press Photo award and a Sony World Photography Award and he was recently named Hasselblad Master of the Year 2012 in the portrait category. We caught up with Rouvre to find out more about work, his inspiration and his approach to photography just in time for the start of our 200 Faces tour which kicks off in Crawley tomorrow.

How did you first get into photography and why did you decide on portrait photography?

In 1988, I enrolled at the Louis Lumière School of Photography in Paris. After this course, I did a brief spell of reportage photography on India’s Narmada dam project, which was published in the Globe. But I was bothered by the photographic relationship with these people and the stolen images that resulted from this reporting, so I very quickly started to photograph my friends instead. The images I took of my circle of friends made up my first book with which I started to canvas Parisian publications. Things took off from there and I received my first few orders for portraits from Libération, then Nova, Actuel, Première, Le Nouvel Observateur etc.

I need a direct, clear and head-on relationship with people. I want to photograph people with their collaboration, to speak to the world through people.

One of your most recent series features survivors from the tsunami that hit Japan in March 2011. What was the most challenging aspect of this project & how did you overcome these challenges?

I was really shaken by this catastrophe and in November 2011, then in February 2012, I went there, without having a clear idea of exactly what I was going to do there. I was moved, above all, by the need to confront this reality that escaped me and that my imagination rejected. I photographed landscapes without even thinking, convinced that it would take time for me to comprehend this calamity. The biggest difficulty and the challenge was to highlight the dignity of those people who had been affected, marked and weakened. I don’t know if I overcame this and managed to achieve it but I wanted to strip back the photo and use less tricks so that I could focus on people’s expressions and let these expressions do the talking.

When faced with the task of photographing people who have lost so much, how did you manage to capture the sense of loss and despair so strongly in your images?

It was just there. All I did was capture the emotions that were already present on their faces. The most difficult part was getting them to agree to be photographed in the first place.

This series of photographs was awarded third prize at this year’s World Press Photo contest and you also won a prize back in 2010 for you images of Senegalese wrestlers. What does it mean to a photographer such as yourself to be recognized with such accolades? How important is it as a photographer to enter such competitions?

It is important, because for a photographer it provides recognition of the profession at an international level and without doubt it is one of the most important and the most prestigious awards to receive. But it is, above all, a way to get your work noticed and to get it circulated in touring exhibitions throughout the world. It justifies the work that I do with the people I photograph; it highlights the work and ensures that it is seen by as many people as possible.

2012 has been a good year for you as you were also selected as a Hasselblad Master in recognition of your contribution to the art of photography. What do YOU believe that your contribution has been?

I think that it is the personal adventure that gets me my projects, from which results a certain sense of maturity and a vision of the world that is becoming more and more personal to me. It is this vision that I share with those who appreciate my work.

In your work you photograph a variety of people from politicians, to celebrities, and sportsmen and women. How does your approach change depending on who you are photographing?

Looking back over the 20 years of my career, I think more than anything that it is time that has shaped my approach as opposed to the models. The aim of the photographs, so whether it is a commission or a personal project, is obviously decisive in how I approach it. It just so happens that I never actually know what photograph I am going to take before I am in the situation, and before meeting with and talking to the model. I always try to establish a direct and spontaneous connection, even if it’s sometimes complicated; for example with a political figure who is used to controlling his image or with a model who simply doesn’t want to “collaborate”.

How much of what makes a good portrait is down to the subject and how much is down to the photographer?

It totally depends on both because a portrait is never done against the model but always with the photographer, the two working together. But what makes a successful portrait? Its strength, its aesthetics, the physical beauty of the model or the setting? It is an alchemy of all of these different elements, or the absence of one of them.

We often confuse being photogenic with a beautiful photo and for me personally, I don’t believe that something is photogenic. Instead I believe in authenticity and in the strength of an image, even if that is to the detriment of formal beauty or the attitude of the model. As a demonstration of this, see picture of French actor Mathieu Amalric, with a bandage on his face.

In 2011, you completed a project for which you were tasked with taking photographs of staff members from Pernod Rickard for the company’s annual report. The images are not what people would expect from staff pictures. Can you explain your intentions?

For me, this project, which I named Blast, was a way of travelling the world through the different origins of those representing the brand (15 countries) and to find my inspiration in painters such as Basquiat, Mondrian, Arcimboldo, Keith Haring and Yves Klein amongst others. For a long time now, this is the Carte Blanche than Pernod Ricard bestows upon the artists it works with and for two years this has also been the case with photographers, the first one being Marcos Lopez. In my mind, I wanted to get completely away from the corporate photo as we understand it or see it, in order to create a more pictorial photo like those of the master painters, whilst at the same time retaining the convivial spirit of the brand.

What do you love most about your work as a portrait photographer?

Meeting people and the human adventures that result.

What is the most challenging aspect of your job?

When my model wants to take the picture instead of me, when they don’t “play” with me, that is to say when they want nothing to do with it, or when they have an idea of the photography that I must take. When we are not together and when there is no reciprocity. The model needs to be curious about the image that I want to create for them.

What advice would you give to young photographers who are just starting out and considering pursuing a career in photography?

Take photos, question them, re-take them…produce to advance.